#4 Consumption Economy and Rate Limits

The dichotomy of unprecedented unemployment as well as startup financing, the hypothesis of the consumption economy, its impact, a game theory lens of stakeholder payoffs, & the power of rate limits.

I spent considerable time in the last month exploring various scenarios of livelihoods and entrepreneurship initiatives in an attempt to “reimagine the landscape of work for rural communities”. A snapshot of my notes on this topic yielded the following:

In conversation with one of the CEOs of a leading social enterprise, he mentioned: “one does not exceed the GDP of the village without ensuring employment and/or entrepreneurship, and infusion of capital in the village economy to support both of those things.”

A former flatmate of mine had this joke: “There are more ways of managing or spending money on something than I have of earning the same money I wish to spend”.

My friend on being asked why a doorstep-delivery bespoke tailoring platform-based startup for women (dress materials, suits, lehengas, and blouses) might work, mentioned: “it will be beneficial for the tailors as they get more customers, as their business has taken a hit during the lockdown. Easy access to tailors will be one of the enabling factors for success”.

A leaked NSSO (National Statistical Survey Organisation) report in November 2019 suggested that consumer spending fell for the first time in over 40 years, on the back of weak rural demand. The average amount of money spent by an Indian in a month fell by 3.7% to Rs 1,446 in 2017-18 from Rs 1,501 in 2011-12.

The thread that binds these four totally unrelated conversations is the same one I use to weave this post. In this post, I try to understand the dichotomy of unprecedented unemployment vs startup financing in current times, my hypothesis of the consumption economy, its impact, a game theory lens of stakeholder payoffs, & the power of rate limits. This is more of a rant than a post.

The Dichotomy - Unemployment vs Growth

As I write this on 12th June 2021 - India has seen over 2.94 Cr Covid Cases and 3.67 lakh deaths since the beginning of the pandemic last year. We are looking at a massive unemployment and hunger crisis in India, a scenario similar to the one that happened last year.

Current Scenario - The Unemployment Crisis

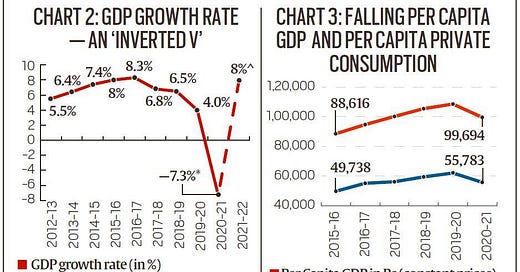

CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a leading business information company) data suggests our current unemployment numbers are at an all-time high, the rate of unemployment crossing into the double digits - with a 12.3% overall unemployment rate, with rural unemployment rates just above 11%.

Definition of Unemployment Rate: This is the unemployed who are willing to work and are actively looking for a job expressed as a per cent of the labour force.

Image: CMIE Unemployment Dashboard

In absolute terms, if we take the 95.33 Cr rural population of India (adjusted to decadal growth rate projections for 2021, Jal Jeevan Mission Data Portal), the unemployment (assuming employment to population ratio of 47% based on the Periodic Labour Force Participation Survey) numbers stand at about 5 Crore.

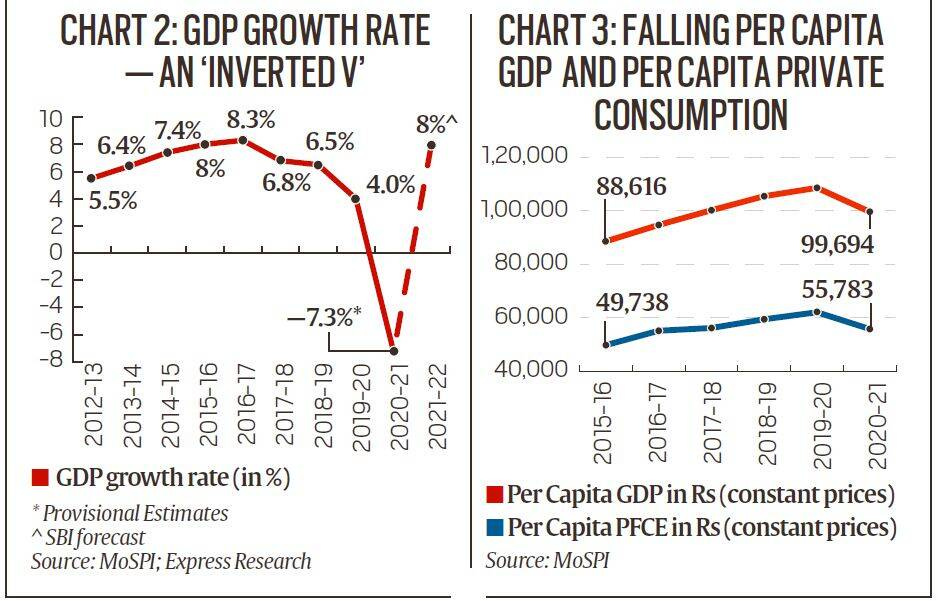

Impact: Assuming GDP per capita to be INR 99694, we get a loss of 5 lakh crore per annum to the GDP.

This is due to, amongst a plethora of reasons - the prevalent reverse migration, the lack of viable employment opportunities in rural India, limited income-generating activities (different from employment opportunities because we can consider entrepreneurship or self-employment can be a viable income-generating activity), limited union budget allocation, and limited access to capital (both debt and equity) in the rural economy.

Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s Budget 2021-22 allocates Rs 73,000 crore for MGNREGA, 34.52 per cent below the Revised Estimate of Rs 111,500 crore for 2020-21. Budgetary Estimate for 2020-21 was Rs 61,500 crore; In 2019-20, Rs 71,686.70 crore was spent on the programme.

The Other End of the Spectrum - Startup Financing and Internet Penetration amongst Consumers

Some opposing trends were also observed on the other end of the spectrum. According to a joint study by the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI) and Nielsen, India now has 504 million active internet users, who are five years or above. This is an interesting snippet from a piece by YourStory:

India continues to be the world’s second-largest internet market after China. But what makes it more irresistible to Silicon Valley companies is that it also happens to be the largest untapped internet market in the globe. With close to 900 million people without internet connectivity still, there’s little doubt that the Next Billion Users are going to come from India.

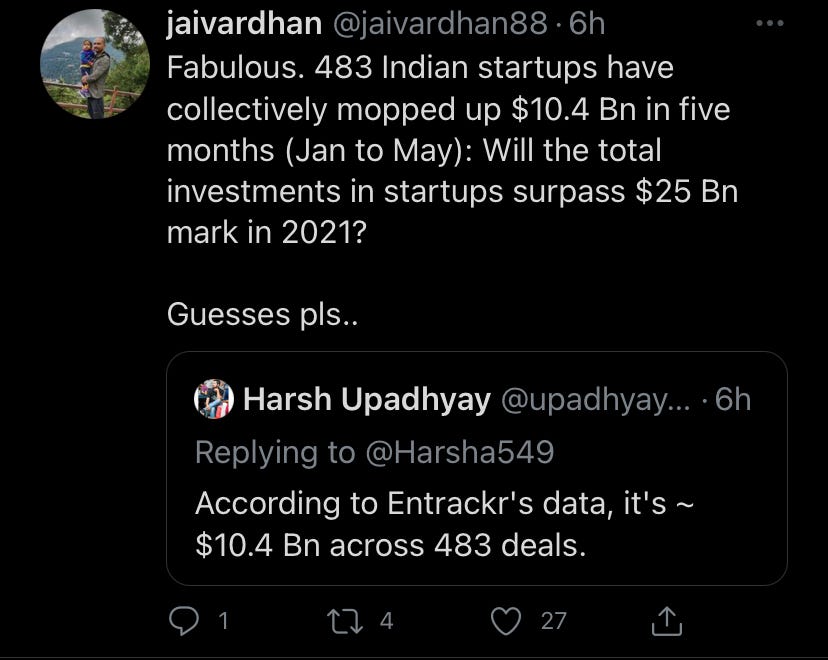

Another very interesting piece of information I came across was the total VC investment in India from January to May 2021 - the same time period that saw one of the largest slumps in unemployment. A total of 483 Indian startups have over USD 10 Billion (INR 73,000 Crores) in venture-backed investments, which is almost equal to the same amount spent last year (the whole of 2020 and even 2019). It is also the same amount of capital allocation made by the Union Government for its flagship MGNREGA scheme.

This brings me to the question, how are we consistently balancing this dichotomy which has one of the worst unemployment crisis in our country’s history on one hand, and the booming startup ecosystem on the other. On this foundation as a rock, I shall build my church, introducing my hypothesis.

The Consumption Economy

My hypothesis is simple.

The rate of consumption has exceeded the rate of income across the middle and lower sections of the socio-economic strata in the Indian society.

Taken in absolute terms, the income of a person or a household in comparison to the consumption of the person or a household might not make much sense. However, if we take the lens of “the rate of change” or “the flow” of both income and consumption, we find the deviation from the standard norms of economics - that income and consumption should go hand in hand, and the trends are similar.

As a reader reading this, I would like for you to take your own example as a case study and see if this hypothesis stands true. Starting 2015 till today (being June 2021), if you calculate your income and consumption patterns on a year-on-year basis, there is a high probability you may find that not only has your consumption patterns increased in due course with the rise in income.

There is also a high probability that the ‘percentage of consumption’ as a part of your ‘total expenditure per annum (not accounting for investments and rent and other typical expenditures’) has also increased. This might be in the form of buying things from Amazon, clothes, foods, electronic items, the quantum of groceries per month, gifts received and given, food deliveries, etc.

If we do a root-cause analysis at a systems view, I attribute one of the key enablers of this problem to the rise of the consumption economy, largely driven by the venture capital industry pouring in huge sums of money, the associated highly-limiting business models, and the increasing reach of the internet enabling the rise of performance marketing.

Enabling Factor of the Startup Ecosystem in India

My friend Darshan Kumar recently shared a very interesting “The Seen and The Unseen” podcast by Amit Varma featuring Sajith Pai, a very well respected venture capital giant in India. You can listen to the entire podcast and notes here. Though I disagree with a lot of what Mr Pai said in the podcast, I still recommend it as a great podcast to understand the world of venture capital, startups, and the consumer economy. This was about a month after Mr Pai wrote his excellent essay deconstructing the venture capital and startup landscape in India over the last 30 years. This is a must-read, and I encourage you to please give it a thorough read if you do want to understand the startup ecosystem in India. An excerpt from the essay is given below:

A look at the playbooks that have evolved in Indus Valley given the forcing functions: these include distinct India1 + India2 approaches in sectors such as Ecommerce, EdTech, Fintech; consumertech startups designed for success in U.S. market a la their B2B SaaS peers; full stack models over marketplaces; SaaSTra or SaaS + Transaction as an approach for Bharat SaaS; reducing reliance on ad-led models etc. I double click on each of these themes or playbooks, to detail out the playbook. Occasionally I speculate on future playbooks.

This one paragraph provides us with the broad strokes of the consumption economy created by these startups for what he terms as the India1 + India2 section of the society (more details are provided in the hyperlink).

A two-track consumer market. Much of the online spending has thus far been driven by these 110–120m (25–30m households) India1 consumers. For a long time, these consumers constituted the limits of the internet in India. But thanks to Jio and cheap bandwidth, we have seen an explosion of less affluent, non-English speaking consumers come aboard the Indian internet. I refer to these consumers as India2. In fact, the India consumer startup ecosystem can be seen in terms of four tiers or stacks.

The larger strategic view of the entire ecosystem and landscape is that the rise of these startups has primarily directed towards tapping the prospective disposable income of the households. It started by expanding the awareness, availability, and access to products and services through eCommerce and consumer tech, which was then followed by innovations in finance (buy now pay later, easy credit) and technology (enabling D2C - direct to consumer). In the last 18 months, we have seen a lot of consolidation of startups (a lot of which do not even have a positive cash flow), and a rise of the blended models such as eCommerce+Fintech (CRED), and eCommerce+Agritech.

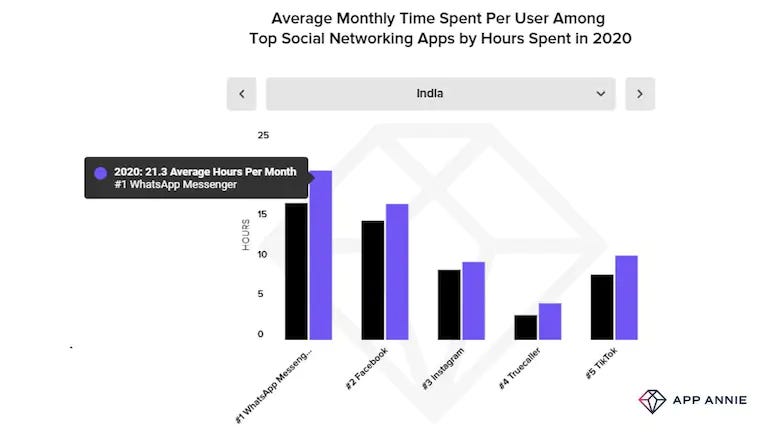

This is accompanied by the rampant adoption of Whatsapp, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and Tiktok amongst the same section of the society (India1+India2), and the innovations in performance marketing that comes along with this. According to the State of Mobile 2021 report by App Annie, a mobile data and analytics platform, WhatsApp outshined other popular apps like Facebook, TikTok, Amazon, MX Player, and more during the pandemic.

This has led to a mad rush for ensuring the target customers are able to view these emerging products and service offerings for them to be able to consume them with ease, reducing friction for the consumer at every stage imaginable.

WhatsApp led the way when it came to average monthly time spent per user among some of the top social networking apps by hours spent last year. According to the report, WhatsApp users in India spent an average of 21.3 hours per month on an average in 2020, a rise of over 20 per cent from 17.2 hours per month in 2019.

Some of the other apps that topped in average monthly time spent chart were Facebook with an average of 17.1 hours per month, Instagram with an average of 9.8 hours per month, and Truecaller with an average of 4.6 hours per month.

Impact of the Hypothesis - Gaps of the Consumption Economy

Just to reiterate, the hypothesis I suggest is -

The rate of consumption has exceeded the rate of income across the middle and lower sections of the socio-economic strata in the Indian society.

The reasons why this is important to talk about this subject is the fact that this imbalance leads to a greater gap in inequality, the erosion of financial capital, misallocation of resources, and negative long-term gains.

What we are currently doing is that we are pushing people and consumers more and more towards consumption of products and services, faster than their capabilities to absorb the said products and services. The primary driver of that capability is the “income parameter”, which includes the very essential “disposable income” parameter. The rise in income is disproportion to the rise in the consumption patterns. At present, this gap is greatly widening the inequality in the India1+India2 segment of people. The consumers are enamoured by the comfort of having everything available at the click of a button at the doorstep and hence are not concerned with the larger picture.

The Power of ‘Rate Limits’

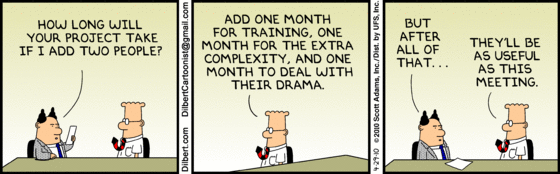

I borrow this from the 40 plus-year-old book called “Mythical Man-Month”

“Just because one woman can have a baby in nine months does not mean that nine women can have a baby in one month” Fred Brooks, author of “The Mythical Man-Month” and the concept of “Brooks’ Law.”

This famous quote by Fred Brooks was an observation on software development processes in the mid-seventies. Yet it perfectly sums up the logic many companies still follow today when faced with various business obstacles.

My take on this is different. Every entity in an existing system has an inherent capacity to provide or receive attributes. This is called the Rate Limit. For example, a tumbler made of glass has a rate limit of 300 ml of water. A tailor can stitch a dress in 8 hours, which the tailor then spreads across a period of 5 days a week. We as humans work 8-10 hours a day for a monthly income. Most entities have a relatively fixed range of rate limits.

The fallacy in the decision-making process is that we tend to ignore the rate limits when thinking at scale, especially at a macro-level. This is particularly relevant to the startup ecosystem. For instance, the example of the bespoke doorstep tailor business idea mentioned at the start of this article assumed that there is a great demand for such a service looking at the total addressable market (also called TAM, which in this case may be the total households in the 6 sq km radius of the location of the tailor). What should be taken into account while looking at the feasibility and viability of the business idea goes beyond the TAM. The rate limits of the tailor donot exceed say 56 orders a month because of the rate limits of the tailor being able to service the transaction. Even though the TAM for that one tailor might be about 1000 households in that geography, the cost-benefits of starting this kind of service is simply not viable due to the constraints of rate limits. The same can be applied to most entities in any system.

The use-case of exhausting rate limits in the Indian startup ecosystem (as rightly put forward by Mr Pai in his podcast) has been the move towards internationalisation, moving into other countries due to the saturation of the consumption patterns in the target customer segment (India1 and India 2). A classic example of this is Zomato. What is also not happening is the transmission to the section of the society under the bracket of ‘India3’ by building their capacities, not just in terms of improving the income parity, but also product design and customer empowerment.

A consumer only has 8-10 hours of work in the 16 waking hours per day, INR xx per month of disposable income (besides rent and investments). Within this rate limit, you have thousands of companies clamouring for a 10-second window for advertisement, or creating products and services reducing the friction of transactions enabling consumption. It is also within the same rate limits that we need to find time and/or the resources to build our own capabilities to increase our income, at the same rate if not higher than that what we consume.

Nash Equilibrium of the Consumption Economy

To understand the continuous rise of this venture capital-backed consumption economy, we might want to explore some of the governing dynamics through a game theory lens. Without going into many details, the synopsis is given below:

VCs and Platforms: VCs and platforms such as Facebook, Google and Amazon come out of this equation unscathed and well off, with high payoffs. This incentivises them to game the system in their favour.

Startups: Meanwhile, startups are engaged in bidding wars for advertisements and share of the rate limits of the consumers, which in due course leaves them high and dry in terms of resources with limited returns. By my hypothesis and estimates, performance marketing yields less than 10 percent of conversion-to-revenue, which is like the best case scenarios.

With more companies fighting for the same slot of the human rate limit, the average price per slot will also increase at a steady pace, making it more expensive for startups. In the long run, this will ensure that small businesses and boutique boot-strapped startups failing due to a lack of resources.

Government and Regulators: They are very important drivers of this ecosystem, and can play a major role in bringing sweeping changes. However, they encourage the VCs and the other big platforms in the garb of showing to the world the increase in FDI and the booming startup ecosystem, without realising that these are the primary drivers of income inequality in the long-run. What also accompanies this is the investments in rural livelihoods and entrepreneurship schemes, the model for which has not evolved to keep up with the times (this is a separate writeup for another day).

Think of a scenario where the government or the regulators enforce Amazon or Flipkart to build 3-5% of their total seller-platform as rural entrepreneurs, or that the Gig Economy giants ensure investments in the Express Industry Council skilling initiatives, or that D2C brands use a percentage of their manufacturing workforce through MGNREGA and skilling initiatives.

Consumers: Ideally, there should be a balance between the utilisation of time and allocation of resources to balance consumption and income based on the rate limits that define us, however, it rarely happens. We have reduced our time to read and learn and upskill ourselves, or even enjoy social connections. The focus has been on consumption.

We only have so many hours and days, and the power of knowledge and information at the click of a button, yet we usually donot spend enough time on building our capabilities that will provide long-term value in terms of increased income and gainful employment in the future. The balance is critical.

Way Forward

Having understood the limitations of our current ecosystem and the existing rate limits of various entities, I believe the focus should be on the following things while we attempt to reimagine income inequality, livelihoods and entrepreneurship, and long-term value creation:

Diffusion of the startup ecosystem in India3.

Building capabilities of consumers for increasing the rate of income.

Innovation of existing initiatives in the Livelihoods and Entrepreneurship domain.

Infusion of private sector capital for long-term value creation in various domains for India3, especially healthcare.

Improving the strategic outlook of relevant stakeholders in keeping the balance between the rate of consumption and the rate of income, especially those in the Government and the financing ecosystem.

And lest we forget, understanding rate limits are important. I end with this great comic strip by Scott Adams.